Mountains of the Moon

Art and science merge in an ongoing project studying the glaciers of Africa’s Rwenzori Mountains. Klaus Thymann’s expeditions in this remote area tell an interwoven story of beauty and enormous loss the poignant imagery simultaneously serves as a tangible scientific resource.

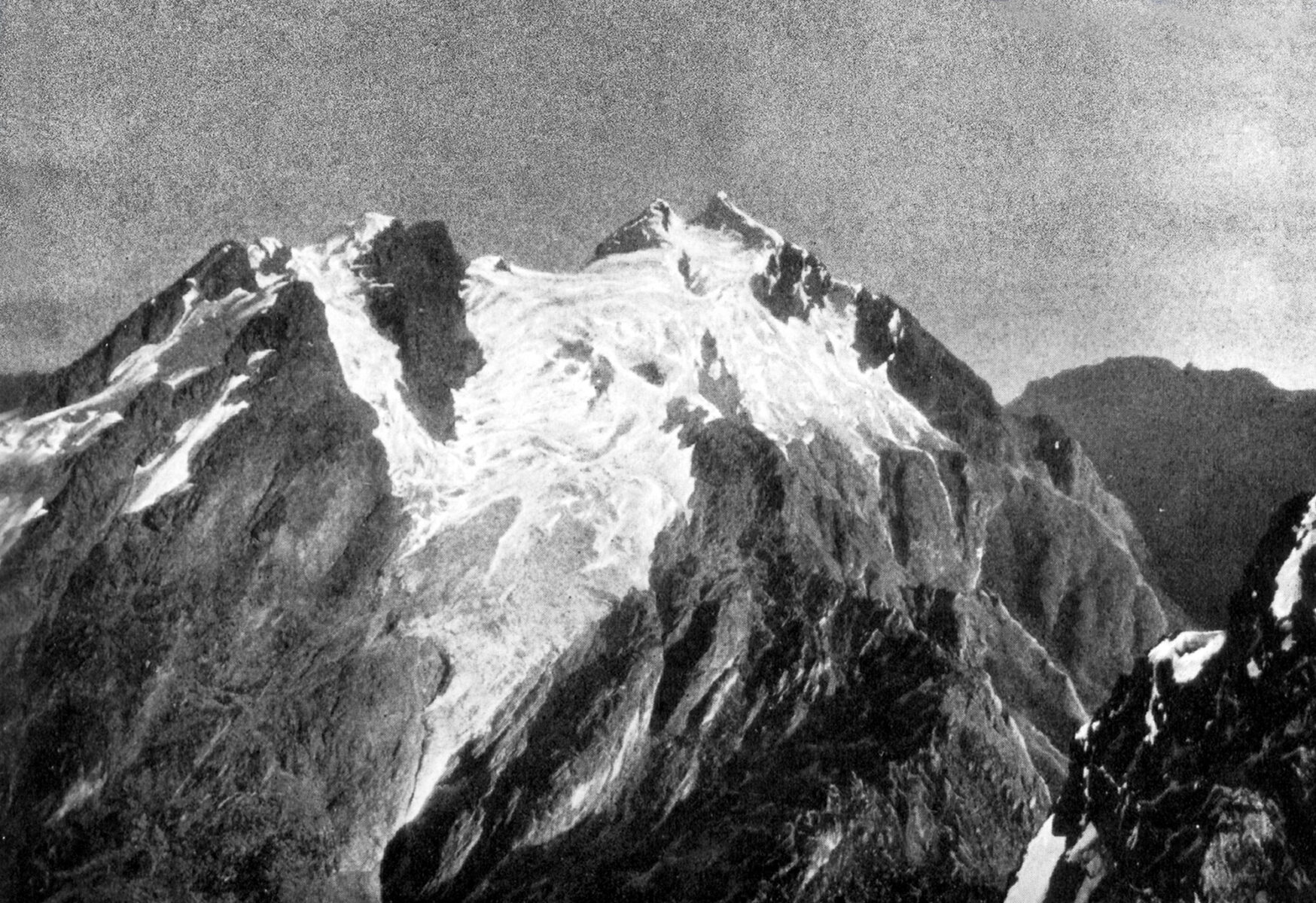

The Rwenzori Mountains are often called the “Mountains of the Moon.” Nestled along the borders of Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo lies one of Earth’s most remote and enchanting regions. The highest peak of the Ruwenzori reaches 5,109 meters (16,762 ft), and the range’s upper regions are permanently snow-capped and glaciated.

There are three towering peaks: Mt Stanley (5,109 meters), Mount Speke (4,890 meters), and Mount Baker (4,843 meters). Except for parts of Mt Stanley, they are all part of Uganda and sit within Rwenzori Mountains National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

For half a million years, the upper altitudes have been home to several glaciers. This is the highest known source of the river Nile. Political instability and civil war in the region meant little information on the glaciers had been collected, and satellite images are virtually non-existent due to dense cloud cover.

In 2012, with these complications in mind, Thymann led his first expedition to seek out the mysterious Rwenzori glaciers. In his demanding physical practice, Thymann brings high-resolution cameras to some of the most inaccessible places on the planet, at altitudes above 5,000 meters, to capture a visual timestamp that marks the human impact on geological space.

To reach the glaciers, Thymann used a decades old map to trek a long-forgotten path across the western DRC side of the mountain. By necessity, Thymann’s team included Ugandan soldiers with military-grade weapons. War and conflict in the region made movement through the area dangerous.

What Thymann found as he reached the peaks was bittersweet; while ice remained on all three peaks of the Rwenzori (Mt Stanley, Mt Speke, and Mt Baker), it was not much. Now, there is even less. Thymann returned to the area in 2022, retracing his steps through his own maps and photographs. The resulting work includes photography, 3D visualisations, and photogrammetry.

This ongoing work seeks to create a consistent data source of the glaciers in the Rwenzori Mountains. Thymann worked with the the Uganda Wildlife Authority, University College of London and other institutions to report the resulting data. The goal is to further the understanding of the impacts of climate change in East Africa, affecting both the Rwenzori Mountains National Park (Uganda) and Virunga National Park (DR Congo), as well as local communities and the wider catchment area.

Elements of the working process include sourcing historical data and collecting new data to calculate current and historic glacier mass balances for the Rwenzori Mountains. Research has shown that very little glaciology data exists, but information can be obtained from historical photos dating back used for comparative images (some to to 1906), maps, and other sources.

That data can be analysed to show a historical correlation between climatic changes and glaciers’ mass data. Additionally – and crucially – it can be used to forecast future scenarios allowing local communities to adapt to climate change.

In a world where the impact of climate change is not uniformly distributed, acquiring historical data on glacier recession in the Rwenzori Mountains has become paramount. Such data is invaluable for comprehending local warming trends and their consequences, not only for the broader global understanding of climate dynamics but to help local communities adapt.

The glaciers of the Rwenzori Mountains have a grim prognosis, but this body of work seeks to continue the narrative by inspiring action-based solutions. By making the invisible visible, Thymann’s work leaves viewers with a deeper connection to the natural world, and connection is the keystone for building change.